by Merle A. Reinikka, FACETS, December 2004

When faceting, I am often reminded of the many variables involved in cutting and polishing different gem quality materials. In this regard, I make notes in reference to these differences–mainly to remind myself of errors made, problems to be solved, and shortcuts that might be taken when repeating a particular design in different faceting materials. I profess no outright expertise, but after several years of learn-by-doing, I’ve come to the conclusion that all of us can benefit from the experiences—good or not-so-good— of one another.

I have spent quite a bit of time at the faceting bench cutting colored Oregon sunstones. These are among my favorite gem materials—primarily because they are readily accessible within a 7-hour drive from my home in Portland, Oregon, but also because they offer a spectacular range of variations in a single gem-quality variety of feldspar.

Colored Oregon sunstones are classed as calcic labradorite, a member of the plagioclase family of feldspar minerals. That terminology may be a little technical for many of us as ordinary, non-scientific faceters. It distinguishes a group of stones, however, that is unique to south-central Oregon. Three different locations in the state, so far, have produced these phenomenal stones: the high-desert region near Hart Mountain, the Alvord Desert near the Steens Mountains, and a forested area north of Burns.

Much has been written about Oregon sunstones—their occurrence in volcanic lava flows; the rarity of the feldspars in their distinctive color variations; and the development of a fledgling commercial market. Least of all, however, has been information on the means by which to obtain the best results when faceting colored Oregon sunstones.

The color that occurs in Oregon sunstones is due primarily to the presence of minute amounts of elemental copper within the crystalline structure of this gem species.

Copper in small trace amounts results in a green hue. In larger amounts, it shows in varying shades of pinkish orange, red-orange, or red. For the faceter, a problem to be met is the dichroism that occurs in ALL colored Oregon sunstones to some extent. Reds, for instance, will show greater or lesser red tones when viewed from one crystal axis to another. But they may also show green on an opposite axis. Well, the problem then becomes—which axis should be cut in order to achieve the best color results? My observations lead me to the following conclusions:

Reds — True reds are dichroic in varying degrees of red color. That is, they exhibit two shades of red, depending on which crystal axis is viewed head-on. Naturally, the more intense red tone is desirable in a finished stone—and so, to obtain the best color (and size, when possible), orienting to the most intense red shade is preferred.

Reds vary a lot. I’ve seen a whole range: fiery-red, red-orange, blood-red, “black cherry,” and even one that had the mellow soft color of rhodolite garnet.

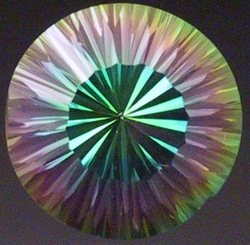

Greens — Greens are invariably dichroic—green on one axis and red or pinkish-orange on the other. To counteract the bi-color (or “andalusite”) effect that results when cutting a brilliant-cut design, I recommend cutting the stone in a step-cut, with steep ends—65 or 70 degrees—just as you would when cutting strongly dichroic tourmaline. I faceted a 4.4-carat green this way, and the whole stone is a pleasing grass-green color when viewed from the table. From the end, though, the red is still strongly evident (a phenomenon which is a source of wonder to viewers who know little about sunstones).

When faced with the necessity of selecting either the red or the green color zone as the pavilion in a brilliant design, always put the red color area in the culet tip. The red color will predominate as reflected color more strongly than the green. If the green is placed in the tip, however, it will often “mix” with the red, resulting in a muddy over-all color.

Here’s an example of what I mean: Years ago, before I had much experience with cutting colored Oregon sunstones, I remember a trip to the public area set aside by the Bureau of Land Management. By chance, my 8-year-old daughter plucked a green sunstone from the wall of a hole where many of us were digging, but which we had overlooked. It had a deep rich green color to it. I wheedled with my daughter to give it to me—but only after I paid her $5 did she part with it! Well, when I cut the stone—mistakenly as a standard round brilliant—the green was in the pavilion, and the finished product was about as exciting as a piece of faceted dead seaweed. A lesson learned.

Bicolors — In faceting marquise, pendeloque and trilliant shapes, it can often be disconcerting to find that the dichroic nature of colored Oregon sunstones will show up with the concentration of the unwanted or alternate color at the pointed end/s of the finished stone. If a bicolor effect is desired, the marquise would be a good choice for a stone with green at the ends and red in the middle. Variations of the Opposed Bar cut can show the same effect. Most designs fashioned in a “brilliant” pattern will also show the two colors—much like the effect obtained when cutting andalusite or strongly dichroic tourmaline.

Many colored sunstones are characterized by a single color spot within a “clear” or yellowish stone. The color spot quite often encompasses only a minor portion of the entire stone. That color spot, however, can determine the resulting color tone and intensity of the finished faceted gem. It is essential to place the culet tip within this color spot in order to “flood” the gem with maximum color.

Often, red color spots are surrounded by a thin “halo” of green. In some instances, this “watermelon” effect can be used to advantage in creating well-placed color combinations that complement one another—rounds and ovals, for example, where the green is held in the center perimeter of the faceted stone.

Schiller — Oregon sunstones have two perfect cleavages. One is evident in the schiller that shows as aventurescence paralleling cleavage planes in some stones. This effect is caused by a concentration of copper platelets. Less evident—but of some importance when it comes to polishing—is the cleavage of the triclinic structure of the crystal itself. Cleavage planes do present problems in the final phase of polishing. One can avoid these situations by orienting 7 to 10 degrees off these known cleavage planes. But when all else fails, try reversing the direction of the polishing lap—or, if available, using a wax lap at slow speed. Cerium oxide, in all combinations of solution or lap make-up, is especially effective in polishing Oregon sunstones. Linde A slurry is my alternate choice, on tin or Corian laps. Spectra (Linde A) or Ultra (cerium oxide) laps may also be useful, though always with the chance of rounded facet edges.

A word of caution regarding cleavage. Only occasionally will this present a problem. The possibility exists, however, when polishing culet facets, that a little too much pressure against the lap may result in the tip of the culet cleaving off if the incipient cleavage plane is too close to the angle at which the culet is being cut and polished. To offset this hazard, it sometimes is beneficial to polish the culet facets a fraction of a degree less than the recommended angle, and then go back to the recommended angle with a very light touch–and polish the remaining unpolished culet tip.

“Purist” faceters may decry schiller as an inclusion. Surprisingly pleasing results can occur in faceted stones when schiller is placed to advantage, though, especially when that same schiller contributes to the color of the finished gem. To at least a certain extent, the presence of schiller in a finished stone reduces brilliance because of the interference of light rays emerging from the stone. That’s sometimes a sacrifice that must be made in order to achieve a desired color or effect. For instance, I fashioned an Opposed Bar cut with two orange-red schiller planes placed perpendicular (vertical) to the crown facets. The schiller planes contributed not only color, but also a pleasing luminescence that literally “danced” across the face of the stone as it was moved. In another instance, evenly spaced schiller planes, placed perpendicular to the table of a step-cut shield shape, provided a one-of-a-kind distinction.

Peach-colored sunstones rarely occur naturally. I’ve found that a single schiller plane—placed perpendicular to the table in an oval cut—achieves just the right color effect without losing much brilliance.

Blues — These are the rarest of the rare. I’ve seen only four or five pieces of rough that could be considered in this color range—mostly blue-green, really. Nevertheless, they are distinctive.

I hope one day to facet one of these.

A truly phenomenal color form I saw at a regional faceters’ conference was a free-form step-cut that weighed about three carats. It was sort of a blue lavender color with an underlying schiller layer. Like nothing else I’d previously seen.

Directional hardness may be encountered in cutting any Oregon sunstone. A heavy hand when cutting is the surest way to discover it. Over-cut facets can be discouraging! Thus, the old maxim, “Cut a little and look a lot” applies fittingly in the cutting process.

Colored Oregon sunstones are fun! They’re fun to dig (even though EXERCISE! is involved); they’re fun to facet (easy to cut and polish, usually); and fun to show off the finished gems (praise and adulation are always good for the ego).